Day 3 (Jan 8, 2026) — The Gospels Read Like Myth Because They Behave Like Myth

Mythic patterns, editorial fingerprints, and the difference between meaning and evidence

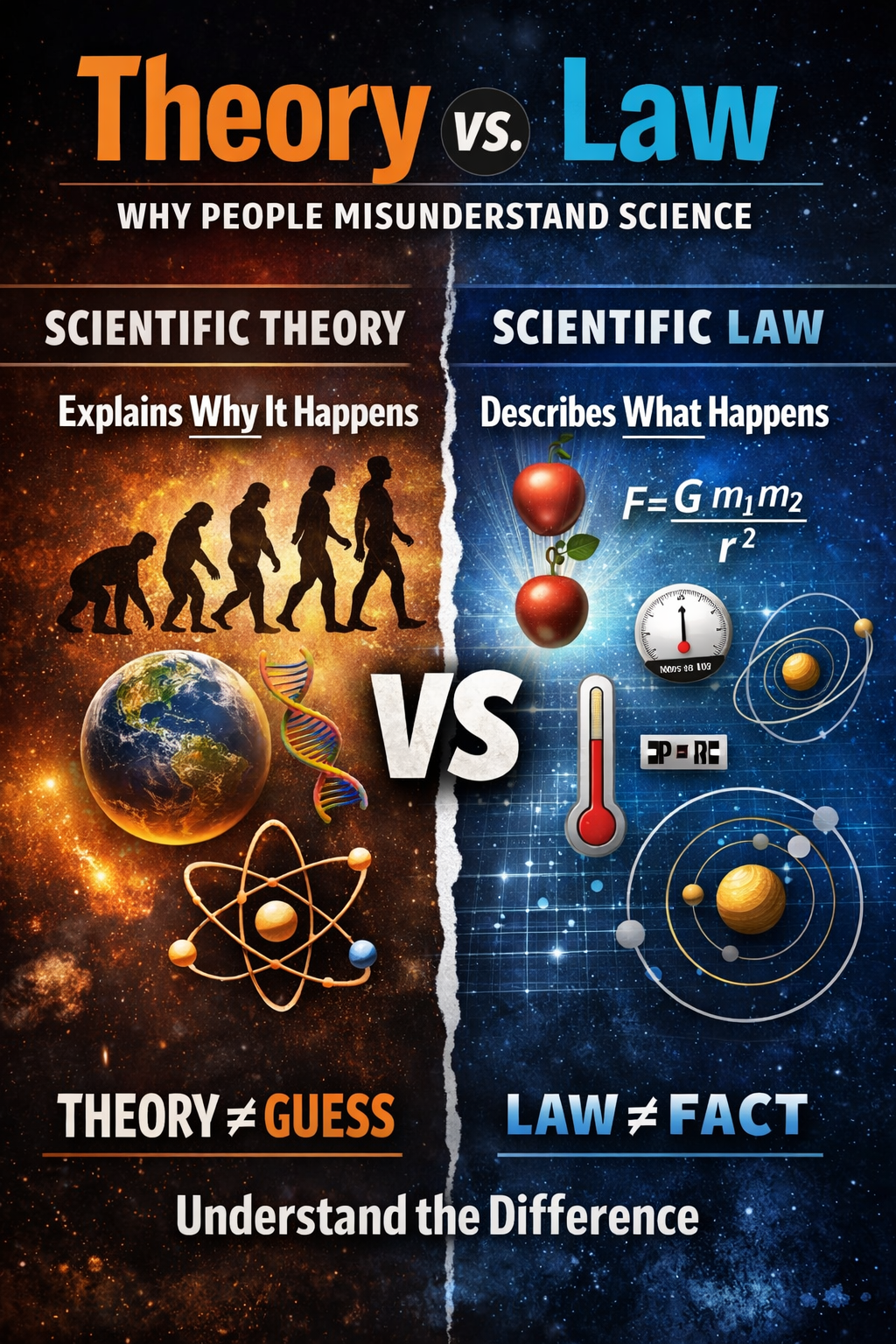

The Weight of Evidence, Not Certainty

In science, no model survives because it is perfect; it survives because it fits the data better than its rivals. You don’t need absolute certainty to see which theory holds more weight—you only need to look at which one explains more with fewer assumptions.

The same principle applies when examining religious texts.

When scholars examine the gospels through the lens of history, literature, and anthropology, they find familiar fingerprints—those of myth-making, editing, and theological storytelling.

This doesn’t mean Jesus never existed.

It means that the Jesus of the gospels—the miracle-working, prophecy-fulfilling, divinely scripted figure—behaves more like a mythic archetype than a biographical subject.

This is not heresy. It’s observation.

The problem is that many people have been trained to see the Bible through devotional, not analytical, eyes.

They grade it on a curve.

The moment one applies the same critical scrutiny used for other ancient texts—like the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Odyssey, or the Bhagavad Gita—the gospels start looking less like eyewitness journalism and more like theological literature.

Why the Josephus Debate Matters

To understand why the mythic framework fits better, look at how Christians defend the historicity of Jesus. The name most often invoked is Josephus, a first-century Jewish historian. His Antiquities of the Jews contains two passages often cited as external evidence of Jesus.

The first, known as the Testimonium Flavianum, explicitly references Jesus as “the Christ.”

But scholars across the spectrum acknowledge that it contains obvious Christian interpolations—phrases and affirmations inconsistent with Josephus’s language and beliefs.

The second, a brief note in Antiquities 20.200 about “James, the brother of Jesus called Christ,” is more restrained. Yet even here, debate rages.

Richard Carrier and others argue that this tag—“called Christ”—may be a later marginal note that entered the main text. The earliest Christian writers, who quoted Josephus extensively, never mention it.

The silence is telling.

If your best “outside confirmation” for the existence of Jesus comes from a text that exists only in later Christian-copied manuscripts, you’re not standing on independent ground. You’re standing inside a feedback loop. It’s like citing your own fan club as evidence of your biography.

The Feedback Loop Problem

The gospel authors wrote decades after the events they describe. Their manuscripts were copied, edited, translated, and harmonized by believers. Every stage of the process reinforced theological coherence at the expense of historical uncertainty.

This isn’t sinister—it’s human.

Communities preserve the version of the story that sustains their faith, not the one that troubles it. That’s how religions stabilize narratives. But it also means that “external” anchors often turn out to be internal echoes.

Even Origen, one of the earliest Christian theologians, admitted the Josephus passage didn’t read naturally. His version in Contra Celsum notes the reference to James but makes no mention of Jesus as “Christ.” The fact that Origen—writing in the third century—felt compelled to argue from inference rather than quotation tells you something about how fragile the evidence really was.

How Mythmaking Works

To understand why the gospels read like myth, you need to understand how myths form. The process is astonishingly consistent across cultures:

- A revered figure emerges—a teacher, prophet, or revolutionary whose death or life becomes a symbol.

- Stories accumulate to explain meaning, justify belief, or interpret suffering.

- Communities compete over interpretations, and editors reconcile contradictions.

- Later writers frame the narrative to align with existing prophecies, cosmic patterns, or numerology.

- Over time, myth becomes memory.

By the time it’s canonized, what began as human storytelling has become divine revelation.

You can trace this pattern in Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and ancient Greek and Egyptian religions. The Christ narrative—miraculous birth, moral teaching, unjust death, resurrection, ascension—fits this archetype so well that scholars like Joseph Campbell and Bart Ehrman both noted its structural parallels to other mythic hero cycles.

The Theological Biography Problem

A “theological biography” is not a biography at all. It’s a didactic story constructed to teach doctrine. The gospels fall squarely into this genre. They contain:

- Miracle Motifs: Healing the blind, walking on water, raising the dead—common features of divine-hero tales in antiquity.

- Prophecy Fulfillment Framing: Nearly every event is tied to “so that scripture might be fulfilled,” signaling literary design, not spontaneous occurrence.

- Symbolic Numerology: Forty days, twelve disciples, three denials, seven sayings—these are not random counts; they’re theological signposts.

- Narrative Parallelism: Matthew, Mark, and Luke recycle structures, scenes, and sayings—sometimes verbatim—showing editorial borrowing rather than independent witness.

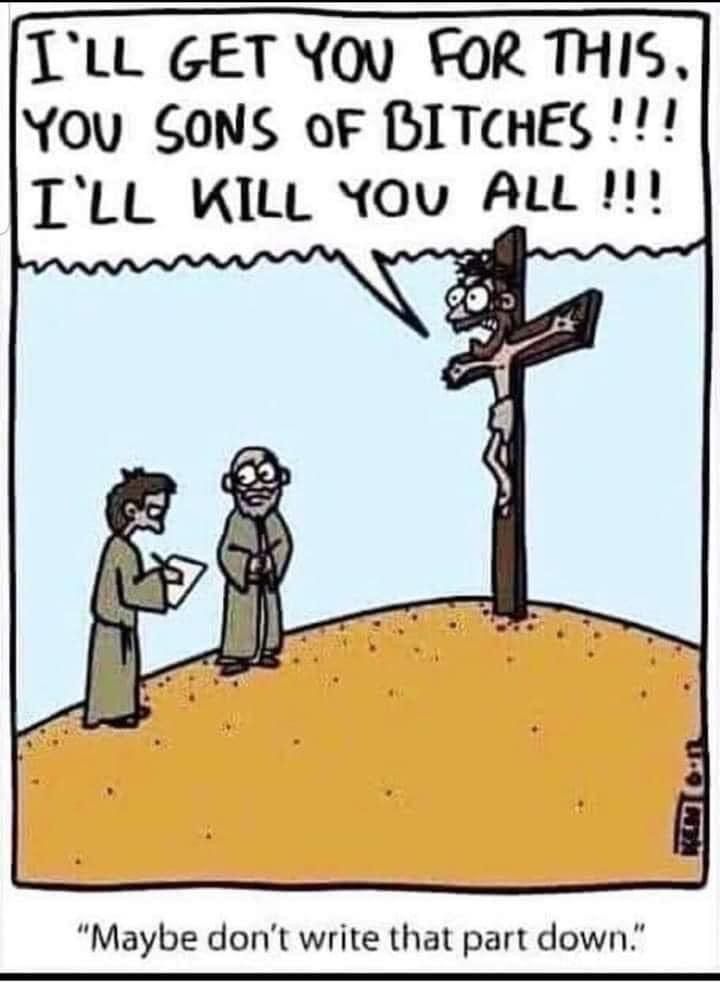

The presence of these features doesn’t disprove faith. It simply identifies genre. The gospels were never intended as modern journalism. They were theological art—sermons in story form.

The Historical Kernel Hypothesis

Even scholars who reject a “mythic Jesus” outright admit that the gospels are mythologized. The debate, therefore, isn’t between “myth” and “history,” but about how much myth.

The “historical kernel” hypothesis holds that a real preacher—perhaps an apocalyptic prophet named Yeshua from Galilee—was later exalted into a divine figure. This process of euhemerization—turning a mortal into a god—is common. It happened to Heracles, to Romulus, and to other founders of cults.

The question is not “Did Jesus exist?” but “Does the evidence we have require a divine Jesus to explain it?” The answer, based on comparative analysis, is no. The simpler explanation—by Occam’s razor—is that stories evolved to serve theological ends.

The Gospel Editing Machine

Textual scholars can trace the evolution of the gospels through redaction criticism. Mark is generally recognized as the earliest. Matthew and Luke draw from Mark and a hypothetical sayings source called “Q.” John, written last, is the most theologically embellished.

Watch what happens across time:

- Mark presents a human Jesus who is reluctant, secretive, and bewildered.

- Matthew recasts him as a new Moses—lawgiver, teacher, and fulfillment of Jewish prophecy.

- Luke universalizes him—gentle, inclusive, moralistic.

- John transforms him into an eternal Logos who pre-exists creation.

That’s not one voice remembering one man.

That’s four communities sculpting four theological portraits for four purposes.

This editorial layering mirrors the way myth solidifies: diverse interpretations gradually converge into an orthodox version, often enforced by councils or creeds.

Comparative Religion 101

Every major religion has a similar pattern of development:

- Buddhism: The historical Siddhartha Gautama becomes “The Buddha,” a cosmic teacher of infinite compassion.

- Hinduism: Krishna and Rama evolve from warrior figures into divine avatars.

- Islam: Muhammad’s sayings are collected, standardized, and surrounded by miracle tales in the Hadith.

- Christianity: A Galilean preacher becomes the incarnate Son of God.

Each case shows the same trajectory: from human teacher to divine archetype.

If you can recognize mythmaking everywhere else, but treat Christianity as a sacred exception, you’re not doing history.

You’re doing theology.

Community Documents, Not Courtroom Testimony

Even conservative biblical scholars admit the gospels were written decades after Jesus’s death. None of the authors claim to be eyewitnesses. Their narratives rely on oral traditions—stories passed down in communities already shaped by belief.

Imagine trying to reconstruct an event today using only sermons, hymns, and prayers written fifty years later by devoted followers. The result would tell you about the community’s faith, not the event’s facts.

This is why historians treat the gospels as community documents—expressions of theological identity, not court transcripts.

The danger arises when societies forget this distinction and start treating faith documents as historical evidence. Doing so doesn’t just distort history; it undermines the credibility of public reasoning itself.

The Problem of Privileged Knowledge

Christian apologists often argue that the gospels deserve special epistemic treatment—that is, they should be read as both faith and fact. But this is special pleading.

If you grant the gospels that privilege, you must also grant it to the Vedas, the Qur’an, and the Book of Mormon. You can’t selectively suspend skepticism for your own tradition.

In a pluralistic society, no religion gets to define truth by fiat. The gospels may be sacred to Christians, but they are not epistemically unique. They operate by the same human storytelling mechanisms as every other scripture.

Recognizing that isn’t hostility. It’s intellectual honesty.

What a Secular Reading Offers

A secular reading doesn’t strip the gospels of value; it simply relocates their meaning. Instead of treating them as eyewitness accounts, we read them as mythic literature—texts revealing the moral imagination of their age.

Seen this way, the gospels become a window into early Christian psychology: fear of persecution, longing for justice, hope for renewal, and the human desire to transform tragedy into transcendence.

That’s powerful. It doesn’t require literal resurrection to matter. It only requires empathy for why people tell stories the way they do.

The Persistence of the Myth

Why does the mythic structure persist even after centuries of scholarship? Because myth does emotional work that reason alone cannot.

The resurrection story isn’t compelling because it’s proven; it’s compelling because it satisfies existential hunger. It answers despair with purpose and death with continuity. That’s what myths are designed to do.

The difference is that modern secular societies can honor those stories symbolically without surrendering to them literally. We can say, “This myth expresses human hope,” without claiming, “This myth is history.”

That’s how you preserve both freedom of belief and integrity of evidence.

The Honest Middle Ground

Some believers fear that admitting mythic elements means abandoning faith. It doesn’t. Faith can coexist with historical awareness if believers accept that myth and metaphor are vehicles for truth, not obstacles to it.

But when religious claims enter the civic sphere—education, policy, law—they must meet the same evidentiary standards as any other claim. That’s the distinction secularism defends.

Secularism isn’t anti-religion. It’s the referee that keeps belief from dictating evidence.

The Broader Implication: Christianity Is Not Epistemically Special

This is the heart of the argument. Christianity dominates Western culture not because it has superior evidence, but because it had historical power—imperial endorsement, cultural inheritance, and institutional continuity.

That dominance has led many to confuse cultural privilege with epistemic superiority. But dominance doesn’t equal truth. It equals influence.

When you apply the same critical method to Christianity that scholars apply to every other religion, the mythic scaffolding becomes obvious. The pattern is not accidental. It’s archetypal.

Reclaiming Intellectual Integrity

The healthiest position for a pluralistic world is not blind skepticism or blind faith, but disciplined curiosity. We should be able to say:

- “This story functions like myth.”

- “This text was edited for theology.”

- “This belief evolved from earlier archetypes.”

And then still allow individuals to find personal meaning in those stories.

A secular society doesn’t need to erase religion; it needs to understand it as culture, not data. That’s the line between freedom of worship and freedom from dogma.

Why This Matters

A society that can tell the difference between evidence and devotion is a society that can reason honestly. When we mistake myth for history, we lose that clarity.

Respecting religion as culture protects everyone. It lets believers live their faith without imposing it on others and lets skeptics analyze it without fear of blasphemy laws or social excommunication.

In short: clarity about myth preserves liberty about belief.

References

Carrier, R. (2026, January 6). T.C. Schmidt on James in Josephus: Apologetics vs. History.

Origen. Contra Celsum 1.47 (Roberts-Donaldson translation).

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are opinions of the author for educational and commentary purposes only. They are not statements of fact about any individual or organization and should not be construed as legal, medical, or financial advice. References to public figures and institutions are based on publicly available sources cited in the article. Any resemblance beyond these references is coincidental.