The Enormity of the Universe: Silence in the Cosmic Void

What the vastness of space tells us about God, aliens, and the silence of the cosmos

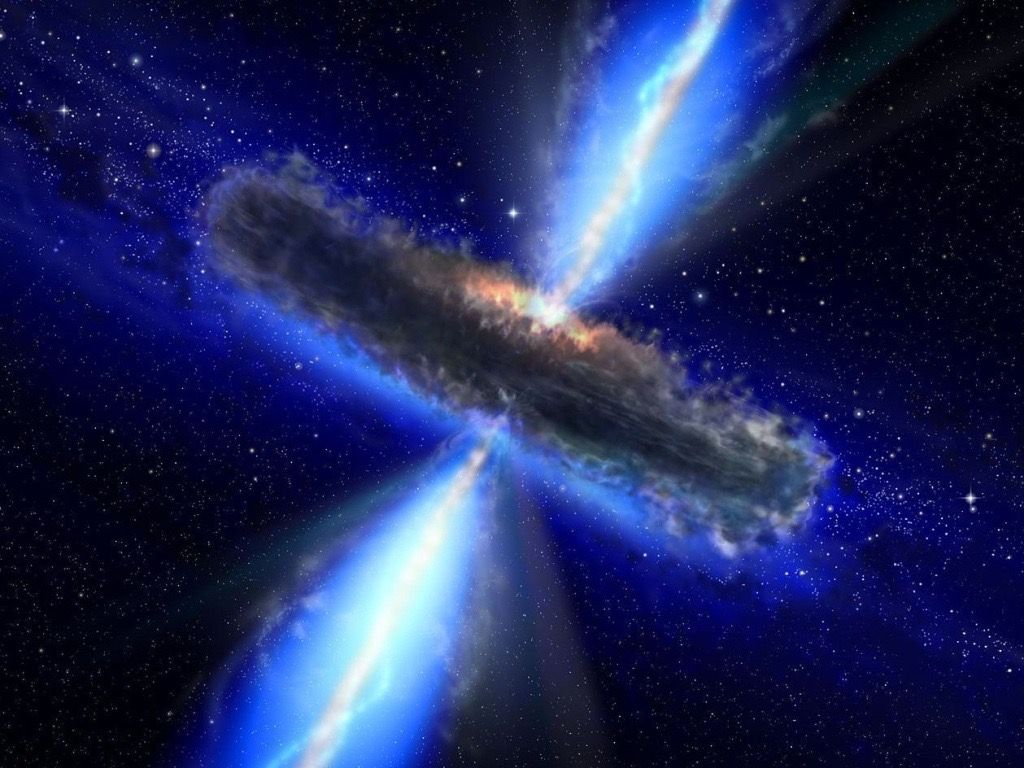

Introduction: Looking Into the Infinite

When we lift our eyes to the night sky, we see more than stars — we see the faint afterglow of an unfathomable immensity. The universe stretches more than 90 billion light-years across, with over two trillion galaxies, each containing hundreds of billions of stars (Conselice et al., 2016). The Milky Way alone houses around 400 billion stars, and orbiting them are trillions of planets, many likely habitable.

This scale confronts us with two questions:

- If God exists as described by religion — all-present, all-powerful, and intimately aware of every human thought — how can such a being possibly “be everywhere at once” in a cosmos so large?

- If intelligent alien life exists, as probability suggests it should, why have we heard nothing from them?

The immensity of the cosmos forces us to wrestle with both theology and science. What does it mean to speak of omnipresence in a universe this vast? And what does it mean that, despite decades of searching, the stars remain silent?

Planets, Stars, Galaxies: Our Cosmic Hierarchy

Planets and Stars

Our planet is one of eight orbiting an ordinary G-type star: the Sun. This star is neither the largest nor the brightest, yet it is essential to us. Beyond our solar system, astronomers have now discovered over 5,000 confirmed exoplanets, with estimates suggesting there may be 100 billion planets in the Milky Way alone (NASA Exoplanet Archive, 2024).

Some orbit within their star’s “habitable zone,” where conditions could allow liquid water — and possibly life. The Kepler mission alone identified thousands of such candidates (Borucki et al., 2010).

Galaxies and Clusters

The Milky Way, vast as it seems, is just one galaxy in the Local Group, which also includes Andromeda and dozens of smaller galaxies. These galaxies belong to the Virgo Supercluster, itself part of a larger filament of superclusters — the cosmic web. The sheer immensity boggles the mind: galaxies grouped into clusters, clusters forming superclusters, and superclusters linked in filaments stretching across billions of light-years (Springel et al., 2005).

The Observable Universe

The cosmic horizon extends 46 billion light-years in every direction. Beyond this lies what we cannot see — regions forever hidden because light has not had time to reach us since the Big Bang. The observable universe contains at least two trillion galaxies, but the actual universe may be infinitely larger.

The Problem of Omnipresence

Religions such as Christianity, Islam, and Judaism claim that God is omnipresent — present everywhere at once. But the more we understand the structure of the universe, the harder this idea becomes to sustain.

Physical Limits

Physics imposes strict limits on movement and communication. Nothing travels faster than light. Even if God is conceived as an immaterial being, omnipresence in a material cosmos requires awareness of every event, from the collapse of a distant star to the synapse firing in a human brain. The scale is not simply large — it is beyond comprehension.

Philosophical Contradiction

To be everywhere at once means to be simultaneously inside black holes, drifting in the void, burning at the core of stars, and hovering in every quantum fluctuation. The concept collapses under its own weight. The larger the universe grows in our understanding, the smaller and more implausible the notion of cosmic micromanagement becomes.

Theologians often retreat to metaphor — “God is spirit, not bound by space or time.” But if omnipresence is not literal, then it ceases to mean anything. The enormity of the universe has stripped omnipresence of its credibility.

The Silence of the Stars: Fermi’s Paradox

If the cosmos is so vast and filled with planets, then intelligent life should be common. Civilizations should have emerged, expanded, and left traces. Yet despite decades of listening with radio telescopes and scanning skies for signals, we hear only silence.

This is Fermi’s Paradox (Hart, 1975):

- The universe is old enough and vast enough for civilizations to arise and spread.

- Yet there is no evidence of them — no signals, no probes, no visits.

Possible Explanations

- Rare Earth Hypothesis: Intelligent life is vanishingly rare.

- The Great Filter: Life may be common, but civilizations destroy themselves before spreading. Nuclear war, climate collapse, or pandemics may be universal roadblocks.

- Too Far, Too Silent: Distances are so immense that signals weaken into noise. Even our strongest broadcasts may never be detected.

- Zoo Hypothesis: Advanced civilizations know we exist but choose not to interfere, treating us like animals in a preserve.

Each explanation carries unsettling implications. If life is rare, we may be alone in an indifferent cosmos. If civilizations self-destruct, our future may be short. If others are watching, they do so in silence.

The Impossibility of Being Everywhere at Once

Religious omnipresence and the idea of ever-present alien civilizations face the same problem: the structure of reality itself.

- Time and Distance: Even if life existed billions of light-years away, its light takes billions of years to reach us. To “be everywhere” is to collapse these distances — something no known laws of physics allow.

- Information Limits: No signal can exceed the speed of light. An omnipresent being would need to violate causality itself.

- Human Scale Thinking: The notion of omnipresence comes from pre-scientific cultures, where the universe was imagined as a dome above Earth. In a cosmos of two trillion galaxies, the concept no longer maps to reality.

If there are beings out there — gods or aliens — they are constrained by the same silence we experience.

Historical Shifts: From Geocentrism to Cosmic Humility

For much of history, humans believed Earth was the center of creation. The Sun, stars, and planets were thought to orbit us.

- Copernicus (1543) shattered this illusion by showing Earth orbits the Sun.

- Galileo (1610) discovered moons orbiting Jupiter, further decentralizing Earth.

- Hubble (1929) revealed galaxies beyond the Milky Way, expanding the universe beyond imagination.

- Modern Cosmology shows we are in no privileged place — not at the center, not unique, perhaps not even noticed.

Every step has diminished humanity’s cosmic importance. If a God exists who oversees everything, His job description has grown from ruling one planet to ruling two trillion galaxies. And the evidence suggests He is silent.

Why Haven’t We Seen Them?

The question of extraterrestrial life mirrors the theological question of God’s absence. If the universe teems with life, why haven’t we seen it? If God is everywhere, why don’t we experience His presence unmistakably?

The answers converge: distance, silence, or nonexistence. Either they are too far away, unwilling to communicate, or they simply are not there.

The Human Longing for Presence

Despite the silence, humans yearn for connection. We direct prayers toward the heavens, hoping someone listens. We build radio telescopes to scan the skies, hoping someone responds. Both acts are driven by the same need: the terror of being alone in the dark.

But silence may be the only honest answer the universe gives.

Conclusion: Living With Silence

The enormity of the universe makes the idea of divine omnipresence or ubiquitous alien civilizations increasingly implausible. The cosmos is not teeming with voices but resounding with silence.

This silence is not despair but responsibility. If no God intervenes and no aliens arrive, then the future of justice, meaning, and survival rests with us. We are the only voice we can rely on in the cosmic void.

Why This Matters

The grandeur of the universe strips away illusions. It challenges the belief in an omnipresent deity who micromanages our lives. It confronts the hope that alien saviors will rescue us. What remains is sobering but empowering: if meaning and justice exist, they must be created by us.

The cosmos does not answer. That silence is both terrifying and liberating.

References

Borucki, W. J., et al. (2010). Kepler Planet-Detection Mission: Introduction and First Results. Science, 327(5968), 977–980.

Conselice, C. J., Wilkinson, A., Duncan, K., & Mortlock, A. (2016). The Evolution of Galaxy Number Density at z < 8 and Its Implications. The Astrophysical Journal, 830(2), 83.

Hart, M. H. (1975). Explanation for the Absence of Extraterrestrials on Earth. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, 16, 128.

NASA Exoplanet Archive. (2024). Confirmed Planets. Retrieved from

https://exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu

Springel, V., et al. (2005). Simulations of the formation, evolution and clustering of galaxies and quasars. Nature, 435, 629–636.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this post are opinions of the author for educational and commentary purposes only. They are not statements of fact about any individual or organization, and should not be construed as legal, medical, or financial advice. References to public figures and institutions are based on publicly available sources cited in the article. Any resemblance beyond these references is coincidental.