Is Blue Ocean Strategy Really All That?

A skeptical look at whether “uncontested market space” is real strategy—or just a fancy way to say “differentiate better."

Introduction

I’ve been circling back to Blue Ocean Strategy lately the way you circle back to an old tool in the garage. You remember it as “the thing that changed everything.” It’s the shiny framework that promised escape: stop fighting in the bloody, overcrowded marketplace and go build a calm little paradise where competition can’t touch you.

And if you’ve ever run a business—especially one where margins get chewed up by copycats, bidding wars, price shoppers, and “my cousin can do it cheaper” people—Blue Ocean isn’t just appealing. It’s emotionally irresistible.

But here’s the question worth asking (and re-asking):

Is Blue Ocean Strategy a genuine business breakthrough… or is it just a well-marketed way of saying “innovate and differentiate”?

The answer is both. And the “both” is where the value is—if you’re willing to treat it like a thinking tool instead of a religion.

WHAT BLUE OCEAN ACTUALLY CLAIMS (WITHOUT THE POSTER SLOGANS)

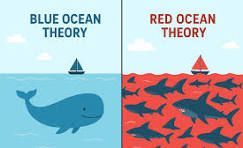

Blue Ocean Strategy, at its core, argues that companies can win big by creating “uncontested market space” instead of battling rivals in existing market categories. It frames the world as:

- Red oceans: known industries, accepted rules, competitors fighting over existing demand

- Blue oceans: market space that’s new (or newly reconstructed), where demand is created rather than stolen

That’s the story. The hook is the promise that you can “make competition irrelevant.”

Now, the authors don’t just say “differentiate.” They say you can pursue differentiation and low cost at the same time—by breaking the usual tradeoff. That’s what they call value innovation: raising buyer value while simultaneously lowering your cost structure, usually by eliminating or reducing factors your industry competes on, and raising/creating factors it ignores.

If you strip away the ocean metaphors, the core claim is:

Stop over-serving the wrong stuff.

Start over-delivering the right stuff.

Do it in a way that scales.

That’s not crazy. That’s good strategy when it’s real.

WHY PEOPLE LOVE IT (AND WHY IT SOMETIMES WORKS)

Blue Ocean gets traction because it gives people three things most strategy talk fails to give them:

- Permission to stop worshiping competitors

Most businesses are competitor-obsessed. They benchmark, copy, “match features,” and eventually commoditize themselves. Blue Ocean basically says: stop playing that game. - A visual, practical toolkit

Strategy canvas. Four Actions Framework (eliminate-reduce-raise-create). Noncustomers. Buyer utility map. Whether or not you use every tool, the framework pushes you to make tradeoffs visible. - A narrative that matches real breakthroughs

Some successful moves really did come from combining elements across categories, not from incremental improvement. The classic framing in the original HBR piece emphasizes reconstructing boundaries and aligning the whole system (utility, price, cost) rather than tweaking one feature.

This is why Blue Ocean became so popular: it’s one of the rare strategy frameworks that’s easy to teach, easy to remember, and easy to workshop with a team.

THE PROBLEM: “BLUE OCEAN” SOUNDS LIKE A PLACE, NOT A PROCESS

Here’s where the hype sneaks in.

A lot of people subconsciously interpret Blue Ocean like it’s a destination:

“Once we find it, we’re safe.”

But the authors themselves describe imitation barriers and the fact that blue oceans attract attention. In the HBR article, they even suggest successful blue ocean moves often enjoy years of advantage, but they’re not claiming magic permanent immunity.

The bigger point: “uncontested market space” is usually uncontested for a reason. Sometimes it’s because nobody thought of it. Sometimes it’s because the market is thin, weird, expensive to educate, or unprofitable.

Blue Ocean can be a gold mine.

Or it can be a swamp.

The framework doesn’t automatically protect you from confusing “no competition” with “no demand.”

BLUE OCEAN VS. REAL STRATEGY (PORTER STILL MATTERS HERE)

One of the most useful counterweights to Blue Ocean is Michael Porter’s basic point: operational effectiveness isn’t strategy. Strategy is about choices, tradeoffs, and building a coherent system of activities that fits together.

Here’s why that matters:

A lot of “Blue Ocean” attempts are really just:

- adding features,

- launching a new service line,

- or making a marketing repositioning claim.

That’s not a blue ocean. That’s “we tried something new.”

A real strategic move—blue or red—requires coherence. It requires that what you do, how you do it, and what you refuse to do all reinforce each other.

Blue Ocean works best when it forces those choices into the open.

It works worst when people use it as a motivational poster to avoid the hard math.

THE BIG CRITIQUE: EVIDENCE, SURVIVORSHIP, AND “CASE STUDY STRATEGY”

A fair criticism of Blue Ocean is that its early popularity leaned heavily on story-driven examples: look at these winners, look at these moves, look at these results.

That’s not worthless—case studies can teach a lot—but it opens the door to survivorship bias. You can always find patterns in winners after the fact. What you really want is: does this framework predict success, or does it only explain success once you already know who won?

Academic discussions have flagged issues like limited scientific validation and weak implementation guidance as commonly cited limitations.

At the same time, research also suggests the debate isn’t “Blue Ocean vs competitive strategy” as an either/or. One SSRN paper argues the two overlap and managers don’t face a clean binary choice—and it attempts to bring more statistical evidence into the conversation.

So the honest takeaway isn’t “Blue Ocean is fake.”

It’s: Blue Ocean is not a guarantee. It’s a lens.

THE MOST COMMON WAYS PEOPLE MISUSE BLUE OCEAN

If you’ve ever watched a team try to “do Blue Ocean,” you’ve probably seen at least one of these:

- “Let’s create a new category” (translation: “let’s invent a market”)

Creating demand is expensive. Education costs money. Time costs money. Most businesses die right there. - Confusing novelty with value innovation

New is not valuable. Valuable is valuable. Value innovation is specifically about aligning utility, price, and cost so the offer makes sense for both buyer and company. - Assuming competition won’t respond

If you find profit, you found attention. The question isn’t whether competitors notice. It’s whether they can copy you fast enough to collapse your margin before you scale. The original HBR article explicitly discusses economic/cognitive barriers to imitation as part of what sustains the advantage. - Doing brainstorming theater instead of making tradeoffs

If your “strategy session” produces a list of things you want to add, you didn’t do strategy. You made a wish list. - Ignoring operational reality

Some “blue ocean” ideas look great on a whiteboard and fail instantly in the field because they don’t fit the team, the process, the capital, or the customer acquisition reality.

SO IS IT “ALL THAT”?

Here’s my straight answer:

Blue Ocean Strategy is “all that” as a forcing function.

It’s not “all that” as a promise.

Its best value is that it makes you ask better questions than your competitors are asking—especially questions about what customers actually value versus what your industry has normalized.

And its biggest risk is that it can seduce you into thinking you’ve escaped economics.

You haven’t.

You’ve just chosen a different set of constraints.

A PRACTICAL WAY TO USE BLUE OCEAN WITHOUT DRINKING THE KOOL-AID

If you want to use Blue Ocean as a real business tool (not a motivational speech), use it in this sequence:

STEP 1: DEFINE YOUR CURRENT RED OCEAN TRUTH

Write the uncomfortable sentence:

- “We currently compete on ______.”

- “Customers choose between us and others based on ______.”

- “Our category norms are ______.”

This stops you from fantasizing.

STEP 2: RUN THE FOUR ACTIONS QUESTIONS LIKE AN AUDIT, NOT A DREAM

- Eliminate: what do we do that customers barely notice, but we keep doing because “that’s how it’s done”?

- Reduce: what are we over-delivering relative to what buyers actually value?

- Raise: what do buyers care about that we under-deliver?

- Create: what could we offer that changes the buying experience, not just the product list?

STEP 3: FORCE THE ECONOMICS

Ask:

- If we raise/ create these things, what must be eliminated/ reduced to fund it?

- What part of this scales, and what part is artisanal?

- If a competitor copies us at 80% quality, do we still win?

STEP 4: VALIDATE DEMAND, NOT ENTHUSIASM

Before you “launch,” prove one of these is true:

- customers will pay more,

- customers will switch faster,

- or customers will refer at a higher rate.

If none of those are true, you don’t have a blue ocean. You have a hobby.

STEP 5: BUILD IMITATION RESISTANCE

Imitation resistance can come from:

- process complexity (hard to replicate operationally),

- brand trust,

- network effects,

- switching costs,

- or scale economics.

If your idea is easy to copy and has no defensibility, it might still work—but don’t pretend it’s “competition-proof.”

THE DIRTY SECRET: MOST “BLUE OCEANS” ARE JUST REFRAMED RED OCEANS

This is where the framework gets humbling.

A lot of “new markets” are just:

- a niche within an existing market,

- a new bundle,

- or a new business model around the same core service.

That doesn’t make them bad. That’s often exactly how real growth happens.

But it means the mystique should go away.

Blue Ocean doesn’t replace competitive strategy.

It’s one method of creating advantage—often by changing what’s being competed on.

And research arguing overlap between blue ocean and competitive approaches basically confirms this common-sense reality: it’s not a binary switch. It’s a mix of strategic logics depending on context.

A SIMPLE “IS THIS REAL?” BLUE OCEAN CHECKLIST

Use this before you let yourself get too excited:

- Are we solving a real pain, or inventing a “need”?

- Can we articulate the buyer utility in one sentence a normal person would understand?

- What do we eliminate/reduce to fund what we raise/create?

- Does the idea still work at scale, or only in boutique mode?

- If a competitor copies 80% of this, do we still win?

- Is the market “uncontested” because it’s new… or because it’s unattractive?

If you can’t answer these, you’re not ready to call anything “blue.”

WHERE BLUE OCEAN IS MOST USEFUL (IN THE REAL WORLD)

Blue Ocean tends to be most useful when:

- Your industry has obvious nonsense baked into it

Meaning: there are costs everyone carries that customers don’t actually value. - Customers are forced into annoying tradeoffs

A “blue” move often removes a tradeoff customers assumed was unavoidable. - The buying experience is broken

Sometimes the innovation isn’t the product; it’s the process. Faster, clearer, less friction, more certainty. - There’s a huge group of non-buyers

When noncustomers exist because the category is intimidating, overpriced, confusing, or inconvenient, reframing can unlock demand.

These are situations where the framework’s questions can genuinely reveal opportunity.

WHERE BLUE OCEAN IS MOST DANGEROUS

It’s dangerous when:

- You’re already losing in a red ocean and want a miracle

Blue Ocean becomes an escapist fantasy instead of a disciplined strategic shift. - You confuse “no competitors” with “no barriers”

New categories often have different barriers: education, trust, adoption cycles, regulation, etc. - You don’t have runway

Market creation takes time. If cash flow is tight, you need a plan that survives the build phase. - You’re a hammer looking for a nail

Some industries reward execution, scale, and operational excellence more than category reinvention.

WHY THIS MATTERS

If you run a business, you don’t need another trendy acronym. You need a way to think clearly while everyone else is reacting emotionally to competitors.

Blue Ocean is useful because it breaks the trance.

It forces you to ask: “What are we doing that doesn’t matter to the buyer?” and “What could we do that actually changes the game?”

But it’s not a cheat code.

Use it like a compass, not a treasure map.

The moment you treat it as guaranteed salvation is the moment it turns into strategy cosplay.

REFERENCES

Burke, A. E., van Stel, A., & Thurik, R. (2009). Blue ocean versus competitive strategy: Theory and evidence. SSRN.

Cziulik, C., Santos, A., & Rozenfeld, H. (2013). A critical analysis on the Blue Ocean Strategy and an approach for its integration into the Product Development Process. ResearchGate (PDF).

Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (2004). Blue Ocean Strategy. Harvard Business Review.

Mauborgne, R., & Kim, W. C. (n.d.). What is Blue Ocean Strategy? Blue Ocean Strategy.

Mauborgne, R., & Kim, W. C. (n.d.). Value innovation. Blue Ocean Strategy Tools and Frameworks.

Mutua, J. (n.d.). A critique of Blue Ocean strategies: Exploring the limits of creating uncontested markets. ResearchGate.

Porter, M. E. (1996). What is strategy? Harvard Business Review.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this post are opinions of the author for educational and commentary purposes only. They are not statements of fact about any individual or organization, and should not be construed as legal, medical, or financial advice. References to public figures and institutions are based on publicly available sources cited in the article. Any resemblance beyond these references is coincidental.